For all the flaws of the

tax reform that Congress passed back inDecember, there's one area where it appears to be working: GettingU.S. companies to bring back the enormous piles of money they havestashed abroad.Now the question is what they will do with it.Before2018, the U.S. government taxed companies' foreign earnings in ahighly unusual way. It applied the 35 percent U.S. corporate rateto their global income (minus foreign taxes paid), but collectedthe tax only when they brought the money home. So companies left itabroad, building a stockpile of as much as $3.1 trillion.The

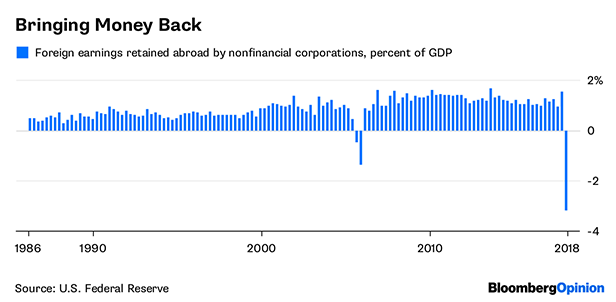

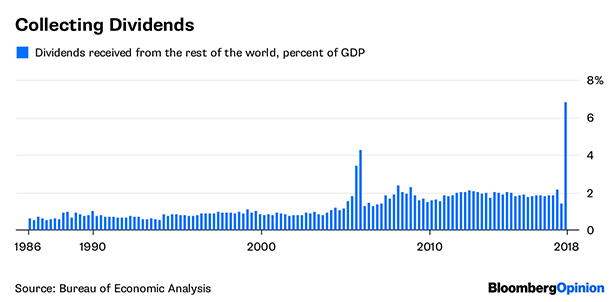

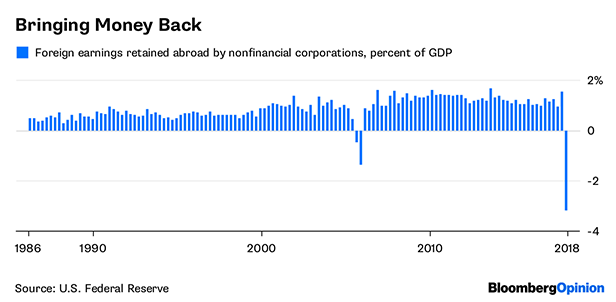

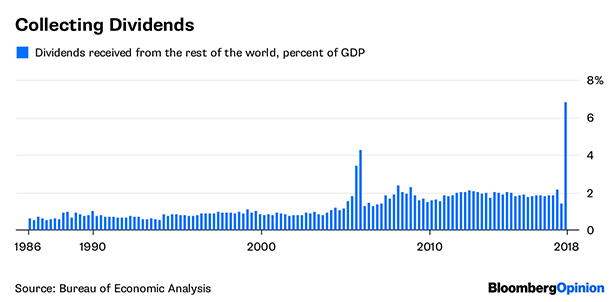

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 changed all that,bringing the U.S. more in line with other countries. For one, itlowered the corporate tax rate to a more competitive 21 percent. Italso largely eliminated taxation of foreign earnings and imposed aone-time tax—15.5 percent on cash, 8 percent on other assets—onwhat companies had already accumulated.The Trump administrationpredicted that the changes would trigger a flood of money back intothe U.S., but many were skeptical. Companies already held so muchcash domestically that they were giving it back to shareholders inthe form of stock buybacks and dividends. Also, many othercountries still had lower tax rates than the U.S., so why notdeploy the money there?Well, an influx seems to be happening.Before 2018, U.S. non-financial corporations tended to add about$50 billion to earnings held abroad every three months. But in thefirst three months of 2018, that number turned to a negative $158billion, according to the Federal Reserve. That's the biggestreversal on records going back to 1946, and much more thancompanies brought back in 2005, the last time the government triedsomething similar. Here it is as a percentage of gross domesticproduct:

Interestingly, companies left extramoney abroad—and received fewer dividends from their overseasinvestments—in the last three months of 2017. This might illustratea perverse incentive that the tax changes created. As of Dec. 20,when Congress passed the reform, corporate executives knew theywould be getting a big break on their foreign stash in 2018.So, it seems, they left more overseas in 2017 to take maximumadvantage.In any case, money is coming back. But what are companiesdoing with it? The real test of the tax reform, after all, will bewhether it prompts the kind of investment that boosts employment,growth, and productivity in the longer run. The Fed data offer someclues.In one positive sign, non-financial companies' capitalexpenditures increased by about $14 billion—or 3 percent—in thefirst quarter of 2018, compared with the previousquarter. They also gave more money back to shareholders: Stockbuybacks were up by about $20 billion, but still well within therange seen in previous quarters. This is perhaps lessencouraging—unless the shareholders find productive ways to investthe money elsewhere.It's still early days, and the true impact ofthe tax reform probably won't be known for years. But give creditwhere credit is due: In terms of bringing money back home, the newtax law is proving some of its critics wrong.

Copyright 2018 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.