There are nations on this earth that tax their citizens far more heavily than the U.S. does. The top spots on the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD's) rankings of tax revenue as a percentage of gross domestic product in 2017 were held by France (46.2 percent), Denmark (46 percent), Belgium (44.6 percent), Sweden (44 percent), and Finland (43.3 percent).

The U.S. tax burden was 27.1 percent of GDP, ranking it 31st among the 36 members of the OECD, the club of the world's affluent democracies. That 27.1 percent includes state and local taxes, and it doesn't factor in the tax cuts signed into law by President Donald Trump in December 2017.

I have trotted out these OECD tax statistics several times over the past few years, mainly because I like trotting out statistics, but also to temper Trump's repeated claims that U.S. taxes are inordinately high. Lately, though, a lot of the talk about taxes has been coming from Democratic politicians hoping to raise them to fund programs they favor, with the increases in most cases targeted at the very wealthy. Which makes this an opportune time, I think, to review how the countries that raise lots more money from taxes than the U.S. go about raising it.

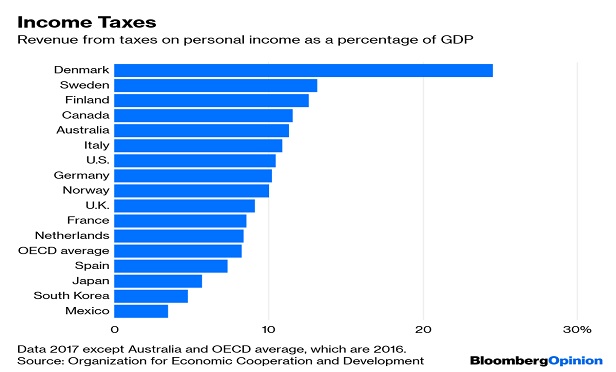

To start, here is how the U.S. stacks up against 15 other OECD nations—the biggest economies plus our neighbors plus some countries (the Nordic ones, mainly) with a reputation for combining high taxes with healthy growth—in personal income tax revenue as a share of GDP.

The U.S. gets much more revenue from personal income taxes than is the OECD norm. But yeah, Finland, Sweden, and especially Denmark bring in even more as a share of GDP. How do they do it? With higher top income tax rates than the U.S., definitely. But also by assessing those top rates on a much wider swath of taxpayers than is the case in the U.S.

Smaller numbers in the right-hand column imply income tax systems that are less progressive—“progressive,” in this case, meaning that rates rise as incomes go higher. In Denmark, the top income tax bracket of 55.8% kicks in at an income of just $77,730 this year. In the U.S., the threshold for the top federal rate of 37% is $510,300. Interestingly, the countries with even more progressive income tax systems than the U.S. (France, Japan, and Mexico) raise substantially less from personal income taxes than the U.S. does.

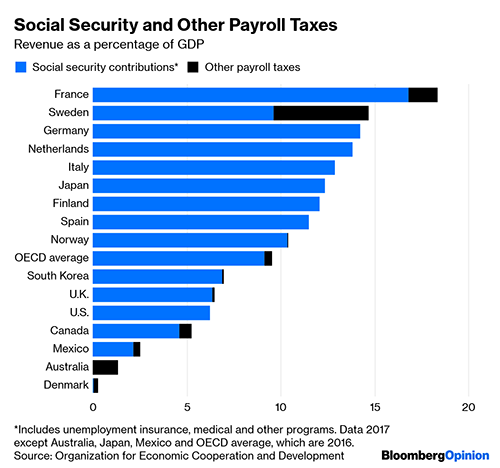

Payroll taxes for retirement savings, health care, unemployment insurance, and other purposes are usually less progressive than income taxes. Some high-tax countries rely quite heavily on them, too. The U.S. less so.

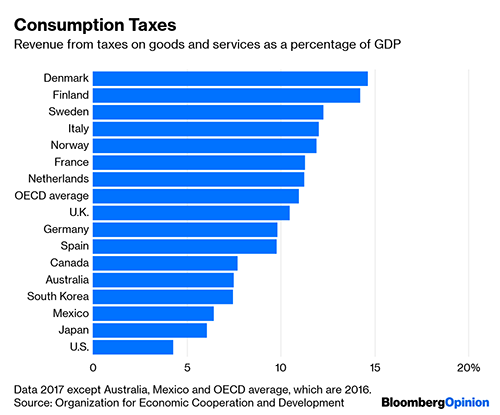

The clearest differentiator between the U.S. and the high-tax countries, though, may be taxes on goods and services. All the OECD countries except the U.S. have a value-added levy that taxes goods and services at every stage of production. The relatively modest consumption tax revenues in the U.S. come from state and local sales taxes and federal excise taxes on fuel, plane tickets, tobacco, alcohol, and so forth.

Lots of economists like consumption taxes because they don't discourage work and investment. The taxes do, however, tend toward regressivity. Poor people spend a larger share of their income on goods and services than wealthy people do.

How about taxing wealth directly? There are so few outright wealth taxes in the world (France had one but ditched it as of last year) that the OECD instead tracks taxes on property, which includes taxes on net wealth but also taxes on real estate, gifts and inheritances, and financial and capital transactions.

U.S. property taxes are mostly taxes on real estate. At 4 percent of GDP, they aren't huge, but in some high-tax localities, they really add up. These are wealth taxes that weigh more heavily on the middle class than the rich because, as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Noah Smith pointed out last month, “rich people hold most of their wealth in stocks instead of houses.” Still, they are wealth taxes, and they're higher in the U.S. than in all but two OECD countries, and much higher than in the high-tax Nordic countries.

Overall, the countries that raise lots more tax revenue than the U.S. tend to have higher top income tax rates but less progressive income tax systems and, it seems, less progressive taxation overall. Their systems help the poor and counteract income inequality more through spending than through tax policy. On the whole, this has worked out pretty well. “There is no clear net GDP cost of high tax-based social spending on GDP,” economist Peter H. Lindert concluded after surveying the long-run evidence from OECD countries in 2003. One of the main reasons for this, he continued, was that “the tax strategies of high-budget welfare states are more pro-growth and less progressive than has been realized.”

The U.S. does have some tax leeway that smaller European countries don't. It's more of a hassle for rich people to leave the U.S. to escape taxation than to leave, say, Finland. And the U.S. is such a huge market that businesses and investors will want to be here whatever the tax structure. Also, there may be good reasons for levying new taxes on the very rich other than raising lots of money. But if raising lots of money is the goal, the tax approach that seems to have worked the best elsewhere involves making most everybody pay.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.