Concerns about cybersecurity are growing every day. Treasury andrisk professionals need to watch for, and guard against, paymentsfraud, ransomware, and data breaches, while also ensuring securityis adequate within third-party vendors of the applications andcloud services their company relies on.

|Meanwhile, the pressure is on from regulators.The latest SEC guidance on the topic encourages public companiesto disclose cybersecurity risks and to describe in financial termsany exposures that are material from a businessperspective. To effectively meet this guidance, treasuryand finance managers should answer some basicquestions about their cybersecurity risk posture:

- What risks do we face?

- What is the financial value of these exposures?

- Which risks pose the largest threat?

- How much should we spend, and where, for best results tomitigate these risks?

Gathering this information is crucial to effective cyber riskmanagement—but finance managers who embark on this journey willsoon discover the Great Cybersecurity Exception. According toconventional wisdom in IT security circles, cyber risks cannot beassigned the same type of dollars-and-cents valuation as otherrisks because cyber risks are too technical and too dynamic, andhistorical data is too hard to find. Instead, cybersecurityprofessionals are often satisfied with designating cyber riskseither red, yellow, or green on a heat map, based on their bestguesses. Or they might show the progress they've made in reducingcyber risks by checking off tasks on a best-practices checklistlike the NIST Cybersecurity Framework.

|For years, cyber professionals have settled for these andsimilar approaches, but that's simply not good enoughanymore. Cyber risk management is undergoing the sameevolution that market risk, credit risk, and other forms ofoperational risk have undergone:

|Market risk was once thought too hardto quantify, especially for derivatives and mortgages, where thereis some optionality. Then we developed options adjusted spread(OAS) models that enable companies to quantify market risk.

|Credit risk. Generalconsensus once held that businesses' counterparty relationshipswere too complex for credit risk to be aggregated, but companiesroutinely do that today.

|Operational risk. In themid-1990s, it was thought that the individual company typicallydoesn't have enough losses or incident data specific to itsbusiness to effectively model its operational loss profile. Riskmanagement professionals fought that issue and have largelyovercome it.

|Strategic risk. Majorstrategic decisions—an acquisition or development of a new product,for example—were once measured only in qualitative terms. Now,yardsticks adapted from financial risk—economic capital andrisk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC)—are routinely applied tostrategic risks as well.

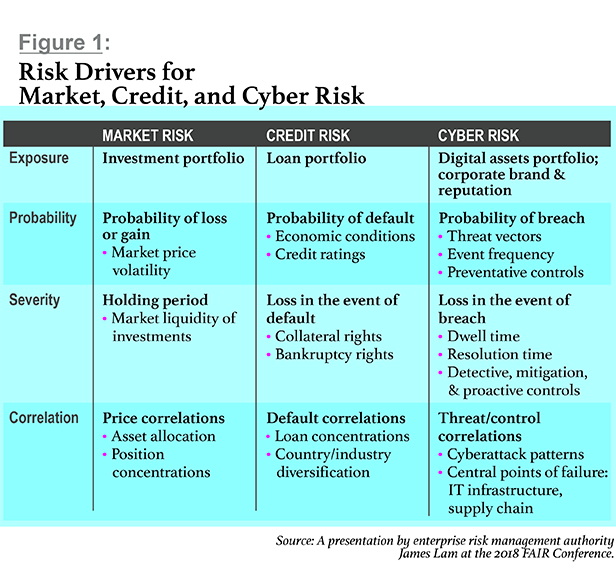

|Through the years, finance professionals and consultants haverepeatedly believed that a particular form of risk could not bequantified, or that companies can't collect enough data toaccurately quantify risks—only to eventually be proven wrong. Theseare the same excuses you'll hear about cyber risks today.Sophisticated cybersecurity managers see that their discipline fitsinto a continuum with other risk disciplines, where new risk modelsand mathematical simulations enable risk management to evolve untilthey provide an effective means of measuring each new form of risk.(See Figure 1.)

|

FactorAnalysis of Information Risk from the FAIR Institute hasemerged as the international standard for quantification of cyberrisks. In use at 30 percent of the Fortune 1000, the FAIR modelenables sophisticated risk management teams to quantify cyber riskin financial terms. A FAIR analysis can enable IT analysts to makerisk-based decisions about cybersecurity, and to communicate thoserisks in business terms to management and other corporatefunctions.

|When paired with standard mathematical simulations, such asMonte Carlo, the FAIR approach becomes a cyber value-at-risk (VaR)model that mirrors the loss distribution approach (LDA) commonlyused in the banking industry to meet capital requirements underBasel II. Similar to LDA, the FAIR model generates anannual loss distribution based on the projected frequency andmagnitude of cyber events. The output of the model is an expressionof cyber risk in financial terms.

|As a result, organizations can:

- assess their risk from ransomware, payments fraud, and databreaches;

- estimate the probability of losses, even absent extensive dataon that specific organization; and

- compare prospective security investments based on return oninvestment (ROI) projections.

Most significantly, companies can use the FAIR model to assesscyber risk in the same way they quantify their other enterpriserisks. This means that cybersecurity risks can be incorporated intothe broader enterprise risk management (ERM) effort, andinvestments in cyber protection can be compared directly againstother potential investments, from both a security and a businessopportunity point of view.

||

Digging into the FAIR Model

The FAIR methodology addresses two longstanding limitations incyber risk analysis: lack of a consistent terminology to discussrisk and lack of a model for estimating losses in financial terms.At its most basic, a FAIR calculation looks like this:

|Risk = Probable frequency x Probable magnitude of futureloss

|A tight definition of the risk scenario is key to a FAIRanalysis. For example, a company might want to analyze the riskassociated with cybercriminals breaching personally identifiableinformation (PII) from a specific "crown jewel" database. Keyfactors in this scenario would include:

- the asset (the PII);

- the threat (cybercriminals); and

- the potential effect (loss of confidential information).

Any FAIR analysis must involve a loss that can bequantified. While that may sound obvious, it hasn't alwaysbeen the case in cybersecurity. Loosely defined "risks"—such as"the cloud" or "hackers"—have often sent analysts down a rabbithole and perpetuated the notion in the industry that cyber risksimply can't be quantified.

|Analysts need to be able to estimate the frequency at which aloss event (such as a data breach or ransomware attack) will occurin a year, as well as the magnitude of financial loss that any suchevent can be expected to cause. If they have this information, theycan estimate how much risk results from the scenario.

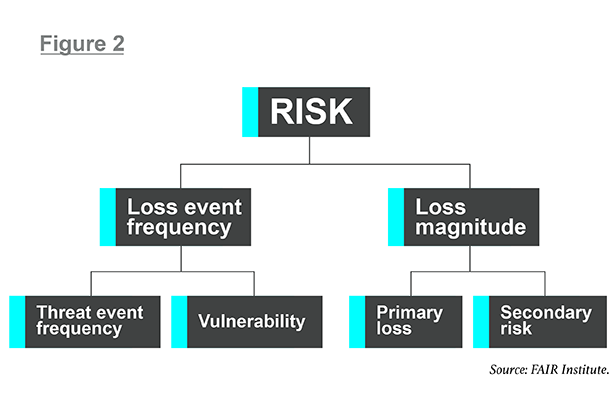

|When they have a workable scenario, with risks they are capableof quantifying, analysts can apply the model, as shown in Figure 2.The FAIR model breaks down frequency and magnitude intosubcomponents. Analysts can estimate each element based oninformation collected from company subject matter experts orindustry reports, then build back up into accurate overallestimates of risk.

|

To continue with our example, the company trying to calculatethe risk to PII in its crown jewel database will need to estimateloss-event frequency—the number of times over the next year thatcybercriminals are expected to successfully access the PII inquestion. Analysts can derive loss-event frequency using the twofactors below it in the model: threat-event frequency (the numberof times they expect, based on experience, that a criminal willattempt to breach the PII database) and vulnerability (theproportion of attempted breaches that are successful). Analysts cangenerate these values for loss-event frequency by running thousandsof Monte Carlo simulations that show probabilistic outcomes for arange of results.

|On the loss-magnitude side, the model guides the analyst toidentify potential costs for the primary loss—which would includeresponse costs, such as IT department efforts to counter thebreach, help-desk staff to handle customer complaints, legal andcommunications team work—and additional, secondary losses, such asbuying credit monitoring for customers, paying fines or lawsuits,or even revenue losses expected because customers demand a contractrenegotiation.

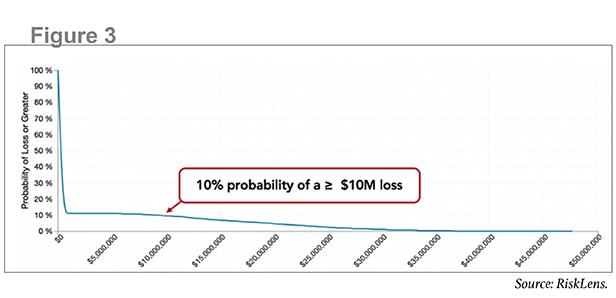

|With the frequency and magnitude inputs, the FAIR model cangenerate a probabilistic statement of how much loss theorganization is likely to experience, as illustrated by the lossexceedance curve in Figure 3. Purpose-built software can streamlinethese calculations. In this case, the model indicates that there isa 10 percent probability that this scenario—a hacker stealing PIIfrom this specific database—will result in a loss to theorganization of $10 million or more.

|

|

Where to Start with FAIR Analyses

A common starting point for organizations is to identify theirtop 5 or 10 risk scenarios, then run those risks through the FAIRmodel. Many organizations are surprised by the results. Seeminglydire, high-magnitude loss events may turn out to be so unlikelythat they shouldn't be a top concern. On theother hand, loss events in which each occurrence incurs a fairlylow cost may turn out to actually present high risk because theyoccur with high frequency.

|If the FAIR software also includes sensitivity-analysiscapabilities, analysts can tweak the inputs and see how they affectthe loss results. What if the company reduces threat-eventfrequency or vulnerability by investing in better controls? What ifit reduces potential secondary losses by reducing the number ofrecords in the PII database?

|Analysts can compare the costs of risk-reduction measuresagainst the probable savings achieved by preventing lossesresulting from cybersecurity failures. Such a cost-benefit analysiscan help companies estimate the ROI of different cybersecurityspending options.

|In addition to the obvious business benefits of more accuratelyestimating risks, FAIR analyses also help IT teams meet externaldemands that they communicate more clearly about cybersecurity.Corporate boards are now asking pointed questions about cyberexposures, in the wake of massive data breaches and ransomwareattacks that have caused material losses to large organizations inrecent years. As an example, the 2017 ransomware attack calledNotPetya cost $870 million for Merck, $400 million for FedEx, and$300 million for Danish logistics giant Maersk.

|The pressure is on from regulators as well. The 2018 SEC guidance on cybersecurity risk managementdirects public companies to disclose their significant risk factorsin financial terms in their reports to the agency. The documentreads like an output from a FAIR analysis. Disclosures shouldinclude:

- frequency of cyber events based on past experience;

- probability and magnitude of incidents (costs, in financialterms);

- adequacy of controls; and

- fines and judgments that might result from a cybersecurityincident.

The guidance document calls for public companies to "provide foropen communications between technical experts and disclosureadvisors." Once, not long ago, that was a nearly impossible ask. Nolonger. Now, translating cyber risks into business and financeterms is a realistic endeavor, thanks to the revolution currentlyoccurring in cyber risk measurement.

|

Nick Sanna is theCEO of RiskLens, with responsibility for the definition andexecution of the company's strategy. In 2015, Sanna championed thecreation of a nonprofit organization, the FAIR Institute, focusedon helping organizations manage cyber risk from the businessperspective. He currently serves as president of the FAIRInstitute, through which he helps risk officers and CISOs get aseat at the business table.

Nick Sanna is theCEO of RiskLens, with responsibility for the definition andexecution of the company's strategy. In 2015, Sanna championed thecreation of a nonprofit organization, the FAIR Institute, focusedon helping organizations manage cyber risk from the businessperspective. He currently serves as president of the FAIRInstitute, through which he helps risk officers and CISOs get aseat at the business table.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to Treasury & Risk, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited Treasury & Risk content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical Treasury & Risk information including in-depth analysis of treasury and finance best practices, case studies with corporate innovators, informative newsletters, educational webcasts and videos, and resources from industry leaders.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM and Treasury & Risk events.

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including PropertyCasualty360.com and Law.com.

*May exclude premium content

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.