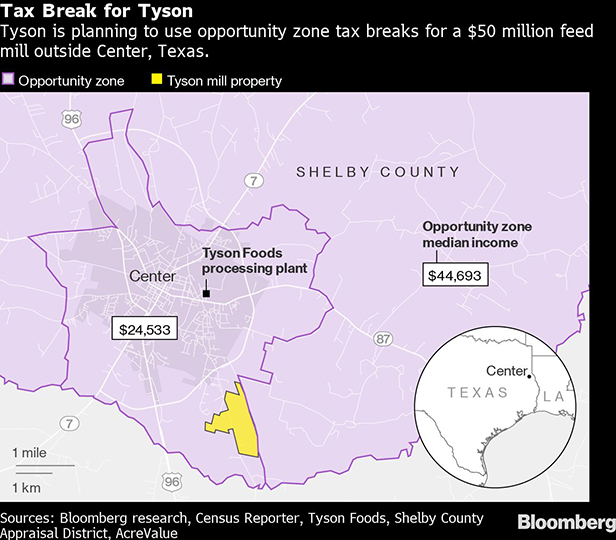

There wouldn't be much of an economy inCenter, Texas, without Tyson Foods Inc. Thecompany has a sprawling chicken-processing plant in town andemploys about 1,600 people in a city of just over 5,000 near theLouisiana border.

|So, when Tyson signaled two years ago that it wanted to build a$50 million feed mill, Center's economic development director, JimGibson, was eager to find a location and suggest taxabatements.

|Before long, Tyson keyed in on a new benefit: a tax break signedinto law by President Donald Trump, aimed at luring newinvestments to thousands of low-income areas across the countrydubbed "opportunity zones." Center and most of the surrounding areasat squarely in one.

|

"One of the people from Tyson said, 'I think we're going to makea run at doing these,'" Gibson recalled.

|That was in private. Tyson—the country's biggest meat processor,with roughly $40 billion in annual revenue—announced its plans forthe feed mill in February as it began to seek aseparate local tax abatement. News reports and minutes from twocounty meetings where the project was addressed make no mention ofopportunity zones.

|The company wasn't required to say anything publicly about itsplans to use the federal subsidy. But like scores ofbusinesses and investors in recent months, Tyson left a faint papertrail. It beat a path to Delaware—where more than two-thirds ofFortune 500 companies have a legal home—to lay the groundwork forclaiming one of the most controversial and generous benefits inTrump's 2017 tax overhaul.

||

Are Opportunity Zones Being Misused?

Once heralded as a novel way to help distressed parts of theU.S., opportunity zones are now being slammed as a governmentboondoggle. The perksare being used to juice investments in luxury developmentsfrom Florida to Oregon. And several reports have shown how politically connectedinvestors influenced the selection of zones to benefitthemselves.

|Tyson's feed mill fits better with what lawmakers intended, butit highlights the lack of comprehensive data on who's claiming thebenefits. Congress is nowcalling for changes to the legislation to boost transparency. Inthe meantime, supporters can point to anecdotal evidence that thebenefits are spurring development in areasthat really need it, and detractors can cite examples ofwaste.

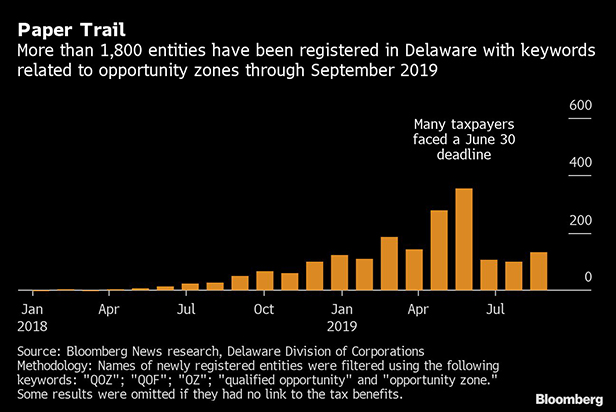

|An analysis of almost 400,000 Delaware Division of Corporationsrecords since the start of 2018 provides a fresh glimpse intowhat's going on. After starting slowly last year—as states selectedzones and the U.S. Treasury Department wroteregulations—the number of filings referencing opportunity zonesaccelerated dramatically. There were at least 356 entitiescontaining acronyms or phrases associated with the tax breaks inJune alone, and more than 1,800 through the end of September.

|

Real estate investors and developers, a group that gravitated tothe tax breaks early, make up a big portion of the list. But therecords show that the appeal is broader, extending to previouslyunreported efforts by Tyson, AT&TInc. and NextEra EnergyInc. Billionaire hedge fund managers SteveCohen and Bill Ackman have also madefilings.

|Tyson said it weighs a variety of factors when looking toexpand, including the availability of workers and infrastructure.Government incentives often play a role, too, and were part of theequation for the new feed mill, said Derek Burleson, aspokesman for the Springdale, Arkansas-based company.

|"Opportunity zones were created to help spur private developmentin economically challenged areas, and we believe this project willdo just that," Burleson said in an email. "We see this as asignificant investment in the community that will create new jobswith great benefits and make a positive impact on the localeconomy."

|A spokeswoman for AT&T, which changed the names oftwo entities after aninquiry from Bloomberg News in July, scrubbing references to"opportunity zones," said the company is evaluating programs toinvest in the areas. NextEra, the world's largest utility companyby market value, declined to comment, as did spokesmen for Ackmanand Cohen.

||

Opportunity for Better Transparency

The filings underscore the lack of transparency surrounding afederal subsidy that could cost billions of dollars, said BrettTheodos, a senior researcher at the Urban Institute whohas studied opportunityzones. And it shows why the government should gather moreinformation both about individual projects and the impact oncommunities as a whole.

|"These are the exact types of investments that we will neverlearn about, absent more disclosure," said Theodos. "We should knowhow the government is spending our money, and it shouldn't fall toinvestigative journalists to figure this out."

|That there's any record at all owes in part to jargon Congressused when drafting the law. Taxpayerswho want to claim the benefits must hold their investments in a"qualified opportunity fund," a corporation or partnership that hasmost of its assets in "qualified opportunity zone" property.

|Lawyers often use shorthand—such as QOF or QOZ—innaming the entities, even though it's not required,said Jessica Millett, head of the tax practice at Duval& Stachenfeld LLP in New York who has structured dozens ofopportunity zone deals. "It just helps you remember what's what,"she said, adding that Delaware was probably seeing a large share ofthe filings because of its longstanding reputation for beingbusiness-friendly.

|Even so, the filings are just clues to what's going on, oftengiving little more than a name and date of formation. Many entitieshave names that are too generic or opaque to scrutinize, such as SMQOZB 3 LLC, created in September. Owners couldn't be identified insuch cases.

|Among those that can be identified are prominent developers ortheir projects. More than four dozen entities are tiedto Starwood Capital Group, Brookfield AssetManagement, or RXR Realty, which are raising hundreds ofmillions of dollars to build in the zones. Socially mindedinvestors are also represented, including a $200 millioncollaborative effort between retired Tennessee Titanslinebacker Derrick Morgan and ActivatedCapital, and another called Arctaris Impact, which haspledged to reportpublicly on its investments and pursue projects that benefit poorcommunities.

|But so, too, are entities that likely stretch what lawmakersintended for the tax breaks. In July, someone used the CorporationTrust Co., a registered agent that handles many Delaware filingsand can help obscure the identities of filers, to create a businesscalled QOZ ART STORAGE QOF 2019,LLC.

|Creating the companies or partnerships is no guarantee that ataxpayer will claim the incentives. Both Cohen and Ackman formedentities in June that were intended to allow them to invest in thezones, but neither has done so yet, according to people familiarwith the filings who asked not to be identified discussing thehedge fund managers' plans.

||

Government Needs to Collect More Data

Just because investors and corporations aren't broadcastingtheir plans doesn't mean they're doing something untoward,said John Lettieri, CEO of the Economic Innovation Group,a Washington nonprofit that helped conceive of and promoteopportunity zones. Companies often hold back information forcompetitive reasons, he added, and sometimes even philanthropicefforts are undertaken anonymously.

|"On its face, it doesn't concern me," Lettieri said. "When youmake a charitable contribution, you can choose to get your nameplastered on a building or choose not to." Even so, he added, thegovernment needs to be gathering more information about investmentsin the opportunity zones so that it can better evaluate whether theincentives are effective.

|In October, the Treasury Department and the Internal RevenueService released new forms that will requirefunds to say which opportunity zones they have property in and todeclare the value of those assets. TreasurySecretary Steven Mnuchin called it an "importantstep toward a thorough evaluation" of the incentives. Butresearchers were quick to point out the shortcomings of the forms,which won't provide information such as the types of projects beingfunded or their precise locations. And because the disclosure ispart of a tax return, the data may never be made public, saidSamantha Jacoby, a senior tax law analyst at the Center on Budgetand Policy Priorities.

|Both Democrats and Republicans in Congress are advancingmeasures to gather more information. Among them is a bill introduced lastmonth by Oregon Democratic Senator RonWyden that would bar certain kinds of investments,including stadiums, and require funds to file detailed publicreports each year.

|More transparency would allow the public to determine whetherthe incentives actually work as intended and discourage bad actors,Wyden said. "This is kind of Sunshine 101," he added. "What I keepcoming back to is: Are the investment dollars largely benefitingthose who are well-off in affluent communities? Or are they tosupport new projects in truly low-income communities?"

| A pair of chicken buildings areseen near a construction site outside of Center, Texas on Monday,Dec. 9, 2019. The site will be the home of a new feeding mill forchickens for Tyson Foods. Sergio Flores/Bloomberg

A pair of chicken buildings areseen near a construction site outside of Center, Texas on Monday,Dec. 9, 2019. The site will be the home of a new feeding mill forchickens for Tyson Foods. Sergio Flores/Bloomberg

Center is the kind of place that could use the money. Thepoverty rate hovers around 30 percent in the Census tract where itsits, making it a shoo-in for the opportunity zone designation. Butinvestors haven't exactly been beating down the doors. "It's justnot the happening spot in Texas right now," said Gibson,the economic development director.

|The community lacks the skilled workforce that attractsbusinesses and real estate development to bigger cities, he said,adding that he couldn't think of an opportunity zone project in thearea, other than the Tyson feed mill.

|Construction of the facility—on a site outside of town andadjacent to a rail line—has already begun, according to Gibson.When it opens in 2021, it will churn out chicken feed for nearbypoultry farms. About 40 people will work there, with an annualpayroll of about $3 million.

|In addition to the opportunity zone benefits, Tyson is getting afive-year break onits county taxes for the mill. But the company decided to forgoanother program that would have allowed it to cut payments to thelocal school district, Gibson said. "It'll be really good for theschools," Gibson said. But, in the end, the number of jobs ispretty minimal, compared with the size of the investment, he added."It's not one of those transformational game-changers."

||

—With assistance from David Ingold, Scott Moritz,Miles Weiss, and Dave Merrill.

|Copyright 2019 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to Treasury & Risk, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited Treasury & Risk content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical Treasury & Risk information including in-depth analysis of treasury and finance best practices, case studies with corporate innovators, informative newsletters, educational webcasts and videos, and resources from industry leaders.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM and Treasury & Risk events.

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including PropertyCasualty360.com and Law.com.

*May exclude premium content

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.