“This may be the peak before it all falls apart again.”

|So said Peter Crane, president of Crane Data, onMonday—the first day of the Crane's Money Fund Symposium, which billsitself as the largest meeting of money-market fund managers andcash investors in the world. He added that he was putting apositive spin on the industry by noting that assets are currently rising in a circumstance whenbalances typically fall. The amount of money in government andprime funds has soared in 2019 to more than $3trillion, the most since the financial crisis, driven by U.S.short-term yields exceeding those of longer-maturing bonds.

|On its face, the impetus to park money in ultra-safemoney-market funds makes a lot of sense. After all,equities are at or near all-time highs, corporate-bondspreads have tightened across the board, and the yield curve isinverted, inevitably raising the specter of a coming recession. Infact, I posited in late March that inversionwould most likely accelerate the dash for cash, after noting thatduring January and February, individual investorsbought $39 billion of Treasury bills at auctions, the mostsince at least 2009.

|

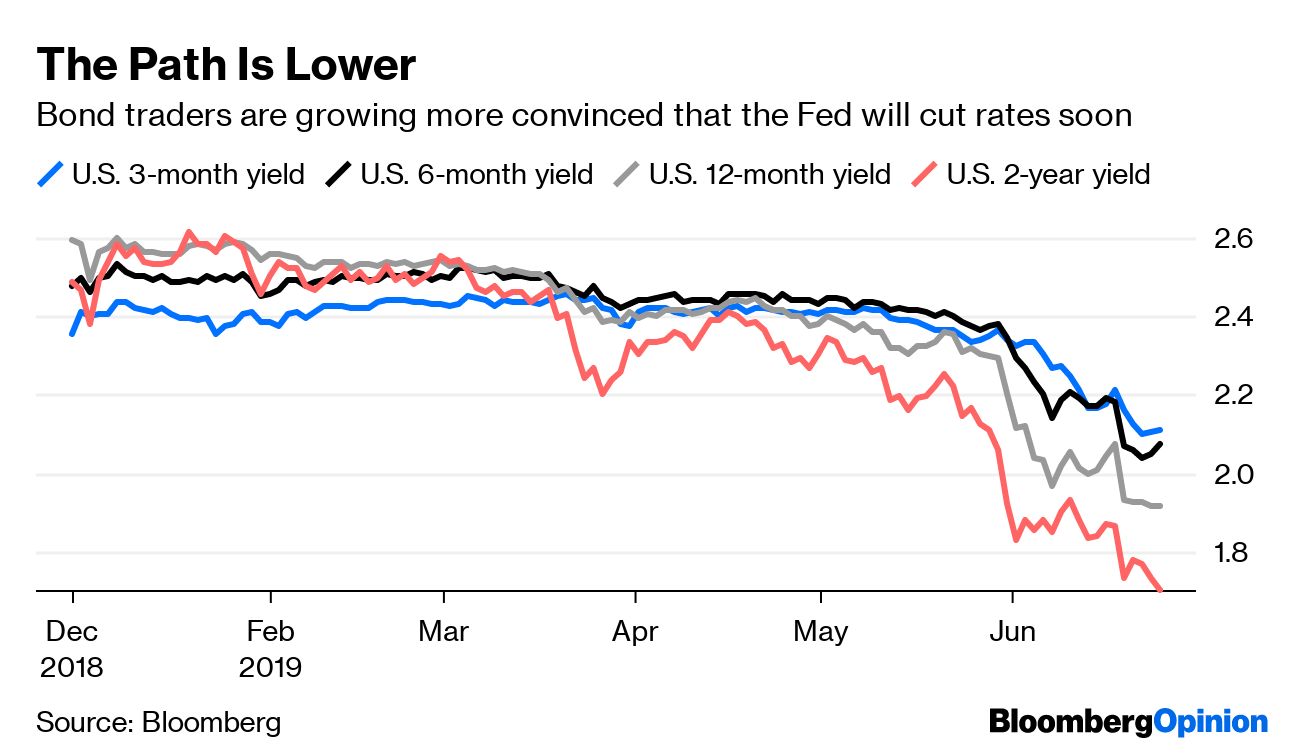

There's one obvious difference between then and now. Threemonths ago, the Federal Reserve was firmly on pause, with officialssignaling they were in no hurry to move interest rates. Now, thebond markets consider a rate cut in July as a virtualcertainty and expect the central bank's benchmark lendingrate to be about 75 basis points lower by the end of theyear.

|Make no mistake: Such steep cuts would most likely roilmoney-market funds. Crane and others at the industry gathering inBoston are putting on brave faces, but the simple truth is that areturn to the post-crisis policy of pinning short-term interestrates near zero would force many investors to withdraw their moneyand seek higher-yielding alternatives.

|The problem, of course, is that those other options are few andfar between. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Marcus Ashworthrecently wrote about the “madness” of 100-year bonds from Austriathat may yield 1.2 percent. Bloomberg News's Cameron Crisedescribed the plight of a friend who had plowed money intosix-month bills around the start of the year and doesn't know whereto invest the principal now that the rate on those Treasuries issome 50 basis points lower. It was 2.38 percent as recently as May30; it's 2.08 percent now.

|It's true that Treasury yields across the board have movedswiftly lower in recent weeks. The benchmark 10-year yield is backbelow 2 percent. The five-year yield, which reached ashigh as 3.1 percent last November, is now just 1.72 percent. Andthis is happening even though the median projection among Fedofficials on their “dot plot” is for unchanged rates in2019 and one cut in 2020.

|

This divergence in expectations between policymakers and bondtraders means the mad grab for yield could only intensify if theFed follows through with lowering interest rates nextmonth. And if that's the case, investors would be better offleaving money-market funds now in favor of Treasuries with someduration.

|Consider the period in 2016 from late January to mid-June, justahead of the U.K. vote to leave the European Union. In thatfive-month stretch, the benchmark 10-year yield fell from 2 percentto about 1.5 percent, providing a total return of 5.4 percent.Two-year Treasuries, by contrast, gained just 0.75 percent, andbills (which admittedly had much lower rates at the time) earnedonly 0.25 percent, according to ICE Bank of America indexes.

|That's hardly an unrealistic scenario for the 10-year Treasurynote. At their core, longer-term Treasuries are priced based oninvestor expectations for the path of short-term interest rates.The Fed raised them to a range of 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent, thenhad to screech to a halt. If they're unlikely to get backto that level in the next decade, and in fact may staysubstantially lower for an extended period of time, then a 2percent 10-year yield looks like a bargain.

|Granted, as Crise points out, it would only take 10-year yieldsrising to 2.23 percent to wipe out an entire year's worth ofinterest. Still, it's hard to see exactly what would push them inthat direction—and, just as important, what would prevent a wave ofdip buyers from swarming in and canceling out the move. For thoseconcerned about market risk, there's still a chance to buy intohigh-yielding certificates ofdeposit. Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s Marcus, forinstance, offers the opportunity to save for as long assix years with an annual percentage yield of 2.95percent.

|Money-market fund managers, meanwhile, still have time to getahead of what appears to be the start of a period of Fed interest-rate reductions. They're goingto “want to have dry powder,” Mark Cabana, head of U.S.interest rate strategy at Bank of America, said at the symposium onTuesday, referring to the ability to handle investorwithdrawals.

|The difficult question remains just how far the Fed will go inlowering interest rates. Chair Jerome Powell, in his pressconference after the central bank's latest decision, notedthat “an ounce of prevention is worth apound of cure” in this era of near-zero rates. (He used the samephrase in a panel discussion on Tuesday.) That could be taken tomean policymakers will act quickly and decisively, and then stop tosee how that flows through to the economy and financial system. Onthe other hand, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, whodissented at the June meeting in favor of lowering rates, said onBloomberg TV on Tuesday that the current situation doesn't call fora 50 basis point cut.

|In that case, money-market rates would be lower buthardly decimated. As Alex Roever, head of U.S. ratesstrategy at JPMorgan Chase & Co., noted to Bloomberg News' Alex Harris, in 2007and 2008, when the Fed swiftly took interest rates to nearzero, “it wasn't the fact that they had to cut rates” thatdamaged the industry but that “the overall level of rates got solow.”

|It has been a slow but steady comeback from the doldrums formoney markets. Historically, according to Roever, theexodus tends to be the same, with outflows starting a year or twoafter the Fed begins to ease. At the same time, no prior period hashad $13 trillion of negative-yielding debtworldwide. Just because there's already been a rush towardhigher yields in the U.S. doesn't mean it can't go further wheninterest-rate cuts begin.

||

Copyright 2019 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to Treasury & Risk, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited Treasury & Risk content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical Treasury & Risk information including in-depth analysis of treasury and finance best practices, case studies with corporate innovators, informative newsletters, educational webcasts and videos, and resources from industry leaders.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM and Treasury & Risk events.

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including PropertyCasualty360.com and Law.com.

*May exclude premium content

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.