With gyms closed, many are turning to alternative exercise regimens, resulting in an uptick in cycling. This means more people are experiencing the challenges of pedaling against the wind. Sometimes you start a ride facing serious wind resistance. As you struggle to keep your legs pumping, you're comforted by the thought of the wind at your back on the return route. Then, somehow, as you turn back toward home, Mother Nature pulls a fast one and you find yourself still pedaling into headwinds.

In business, we have all felt this way at times. Rarely, though, have so many industries faced such strong headwinds simultaneously. This pandemic has presented business leaders with an assortment of difficult decisions. Unfortunately, challenges will continue to arise as we enter the bumpy road to recovery. Government guidelines may help, but ultimately executives will have to make difficult choices about when to reopen operations; how to bring back furloughed workers; when to bring remote workers back on site; and when it's safe to resume business travel, sales conferences, and other important activities.

As executives make these and myriad other decisions, they need to prioritize two key objectives. First, of course, is the health of employees and other stakeholders. And second is management of cash flow, debt leverage, and liquidity to ensure that the business survives in the immediate term. Achieving both of these objectives requires considerable transparency and communication with employees, customers, suppliers, and others who need to stay informed as the crisis and recovery evolve.

For companies that have been particularly hard hit or that started the crisis with a heavy debt load, these two priorities might require management's full attention, rendering superfluous any other possible objectives. However, many executive teams will find that once they have a handle on employee health and corporate solvency, they have the bandwidth to take additional actions that better position their organization for long-term success. In fact, the upside-down business environment makes this a good time for organizations to consider upgrading facilities and equipment, increasing supplier diversification, and launching products or services that may not have made sense in the past.

Why might the current environment enable difficult strategic decisions? Consider the situation that an energy services company found itself in several years ago. Senior executives were struggling with how best to implement a new incentive plan for management. Business unit leaders had been paid very well during the recent industry boom and were likely to reject any new incentive designs. Then the price of oil fell from $100 per barrel in June 2014 to under $50 in December 2014, to less than $30 in 2015. As incentive plans fell out of the money across every business unit, managers became more willing to consider changes to their incentive compensation.

Similarly, the current business climate should increase organizations' willingness to consider changes to the status quo. One area in which this may play out is decisions around stock buybacks. (More on this important topic to follow.) Another is pursuit of any new business opportunities that emerge in the crisis.

How to Be Opportunistic

All the upheaval, loss of productivity, declining profits, and unemployment collectively present quite an obstacle to commercial success. At the same time, the cracks in the system generate opportunities for innovation, creativity, and new business models. While playing defense may be the best option for many companies, others stand to benefit substantially from viewing the economic crisis as a chance to prepare for the future.

Amazon, for example, plans to plow nearly all its expected second-quarter profits back into the business by investing heavily in staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE), and new areas such as healthcare and medical testing. This is, of course, a large gamble, as fears of a prolonged global recession linger. But Amazon is well-known for both strategic pivots and aggressively reinvesting in its businesses, and its latest bets just might pay off.

Amazon, for example, plans to plow nearly all its expected second-quarter profits back into the business by investing heavily in staffing, personal protective equipment (PPE), and new areas such as healthcare and medical testing. This is, of course, a large gamble, as fears of a prolonged global recession linger. But Amazon is well-known for both strategic pivots and aggressively reinvesting in its businesses, and its latest bets just might pay off.

Indeed, the investment and strategy decisions that corporate leaders make over the next few quarters will likely have an outsized effect on determining which companies become winners during the recovery and the next economic boom cycle. Few businesses will find as much upside in the pandemic as Amazon has, but most management teams will benefit from considering these areas of possible opportunism:

Shift toward a more digital-centric business model. Retailers with a heavy brick-and-mortar footprint are struggling right now. Their executive teams could use this time to commit serious resources to improving their online presence. Many consumers who weren't Internet shoppers in the past have increased their online purchases, and these behaviors will likely endure.

Companies should also consider less obvious opportunities to convert to an online model—not just to hasten recovery and prepare for the next crisis, but because Internet-oriented business models tend to be more valuable. Long before we were locked out of our gyms, Peloton created a service that gives subscribers the feeling of having a personal trainer without any need for physical contact or geographic proximity. Peloton's EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization) is still negative, but apparently investors believe in the company's future. It's currently valued at more than six times revenue, which is higher than four out of five S&P 500 companies.

Take advantage of demand droughts. Face masks, hand sanitizer, Clorox wipes, and even toilet paper remain hard to come by. But other products—including many types of equipment and heavy machinery, vehicles, and most luxury goods—are facing extraordinarily low demand. Because their producers are desperate to make a sale, some of these items are available at a fraction of their cost a few months ago.

So this is a great time for procurement folks to identify every category and major item that the company purchases under normal conditions, and to determine which of those may now effectively be on sale. Even inventory and manufacturing inputs may be available at particularly attractive prices. Taking advantage of a good deal helps the seller, whose survival may depend on securing immediate cash inflows. And for the buyer, it may present the opportunity for equipment and vehicle upgrades that were hard to justify previously, when prices were higher.

Initiate long-delayed maintenance. In recent years, when the economy was strong, the opportunity cost of shutting down a busy production line led some companies to delay routine maintenance activities. This is never a good idea; deferred maintenance is a sign of chronic undercapacity in a business, which often results from excessive sweating of assets. (See the article "Be Cautious About 'Sweating Your Assets.'") Nevertheless, it is relatively common.

For companies that have neglected maintenance, now is the time to tackle that backlog. It may also be a good time to go one step further and upgrade equipment, with the goal of improving efficiency and expanding operational capacity. Businesses that have built up excessive inventory due to a drop in demand for their own goods may find that the crisis presents an opportunity to fully shut down lines for maintenance and upgrades.

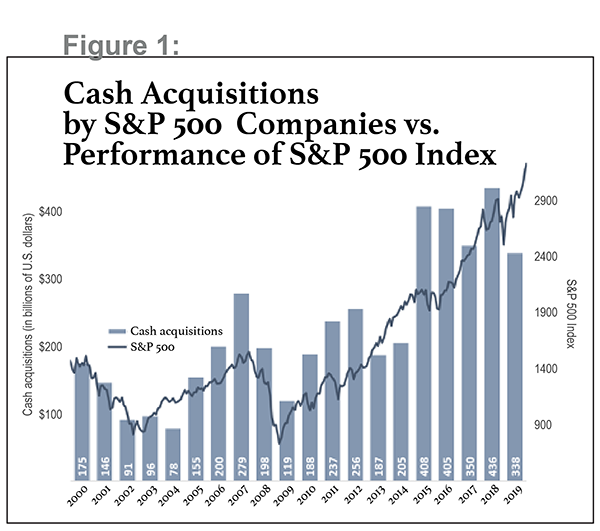

Consider mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Those with adequate resources may also consider buying a competitor at an attractive price. Everyone knows to buy low and sell high, but that's often easier said than done. Figure 1 shows that most acquisitions happen when they are relatively expensive. Far less is spent on acquisitions when businesses are "on sale," as in 2002–2003 and 2009. Although the second quarter is still unfolding, Q1/2020 saw a substantial drop in mergers and acquisitions, both in the U.S. and globally.

The board of directors for the M&A target business may demand a higher premium on a sale during a downturn. But our research shows that acquisition premiums really don't matter—the absolute price is what really counts. (See "Do Acquisition Premiums Matter?")

Look at options for organic growth. Organic investments typically follow the same pattern as M&A, with companies quick to expand capacity at the tops of cycles and hesitant to soak up excess capacity from others at fire-sale prices during downturns. But, over the cycle, organic investments made around the troughs often deliver better returns, since they tend to cost less.

Barriers to Tapping Opportunity

Sometimes companies fail to capitalize on opportunities during a downturn due to recency bias—business leaders expect recent conditions to persist much longer than they actually do. But the primary reason companies are not more opportunistic when the economy declines is that their high levels of debt and other fixed liabilities magnify the broader risk created by the economic conditions.

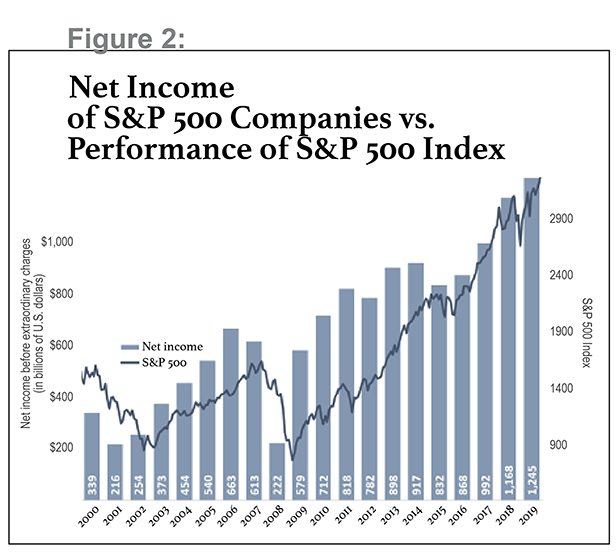

To provide some context, the current members of the S&P 500 generated a total net income before extraordinary charges of $9.2 trillion over the 10 years ending in 2019. This is more than twice the same figure for the prior decade, and it fueled the long bull market shown in Figure 2. Moreover, these businesses' aggregate operating cash flow from 2009 through 2019 was $16.7 trillion.

With all this income and cash flow, companies might have paid down debt so that they would be ready for the next downturn. Unfortunately, most took the opposite approach. Their total debt increased by $3.1 trillion, or 47 percent, to a whopping $9.5 trillion at the end of 2019. Corporate executives obviously didn't know a pandemic would be coming, but every economic boom comes to an end for one reason or another. As they say, "stuff" happens.

Entering an economic downturn with high debt levels creates significant risk to organizational survival. And in the recent past, the most common reason companies end up in that situation has been the corporate addiction to stock buybacks.

Weighing Buyback Risk

Over the past decade, large public companies have bought back about $5.1 trillion worth of their own stock, which is 1.64 times the size of the increase in their total debt load over the same period. If these businesses had not expanded the size of their buybacks compared with the preceding decade, their total debt would have been about flat. For most of these companies, pairing the earnings and cash flow growth of 2009 to 2019 with a steady level of debt would have provided the financial flexibility to be opportunistic in the downturn we've now entered.

Fortuna Advisors developed a Buyback ROI measure nine years ago. Since then, we have published numerous rankings showing that many companies have been pretty bad at timing their buybacks. This ends up benefiting the investors who sell shares and harming those who stay. In one study, we even showed that the more a company improves its earnings per share (EPS) using buybacks, the more its price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple declines. That's a disconcerting signal, to say the least.

Some executives say investor pressure requires them to distribute cash as soon as they get it, though this sentiment seems to be changing. Our recently published 2020 Fortuna Advisors Buyback ROI Report introduces a "Buyback Fitness Test" that companies can use to evaluate whether they are good candidates for buybacks. The framework sorts companies into three buckets:

- Volatile risk group. These highly cyclical and volatile companies should pursue buybacks only under the most favorable of circumstances and never use debt to finance them.

- Opportunistic investment group. These are more stable businesses that have large, variable reinvestment needs. They shouldn't risk missing investment opportunities because they gave too much capital back to shareholders.

- Buyback group. These companies are stable and don't have significant investment opportunities. Buybacks can be an important tool for these businesses, but effective timing remains critical to ensure that shareholders who stay benefit, at the expense of those who sell—rather than vice versa, as has been the norm over the past decade.

Embracing Opportunity

Opportunities created by the Covid-19 crisis will vary substantially, depending on industry, company size, demographics, and a host of characteristics of the individual business, as well as external conditions. While the scale and scope of Amazon's current investments may come to exemplify forward-thinking opportunism during a crisis, what works well for one company may not work for others.

Still, many public companies would benefit at least from Amazon's nimble approach to reallocating capital when market conditions change. Many of these large corporations fail to strategically pivot and adequately fund up-and-coming opportunities due to organizational inertia and inefficiencies in investment decision-making processes. Addressing these cultural and organizational barriers to better resource allocation and decision-making may also require deep thinking about company culture and the incentives and processes that inform it.

Virtually every firm that survives the current pandemic will be presented with opportunities along the way, as a result of changing conditions, markets, and business models. And some will likely absorb market share from competitors whose business models were less optimized for the crisis. Organizations that explore and capitalize on these opportunities should find themselves in a strong competitive position once the economy starts expanding once again.

Historically, this type of big thinking has tended to yield outsized results for many of America's greatest companies over the long term.

The authors wish the very best to all readers. For those affected by Covid-19, we wish you and yours a speedy and complete recovery. We would also like to thank everyone who has generously donated time and/or money to support our communities and the ongoing efforts to fight this pandemic.

Gregory V. Milano is an expert in capital allocation, behavioral finance, and incentive compensation design. With nearly 30 years' experience in management consulting, he has specialized in promoting an "ownership culture" in large corporations through innovative performance measurement and managerial incentives. Milano is currently the founder and CEO of Fortuna Advisors LLC. Before founding Fortuna Advisors, he was a partner at Stern Stewart and a managing director at Credit Suisse.

Gregory V. Milano is an expert in capital allocation, behavioral finance, and incentive compensation design. With nearly 30 years' experience in management consulting, he has specialized in promoting an "ownership culture" in large corporations through innovative performance measurement and managerial incentives. Milano is currently the founder and CEO of Fortuna Advisors LLC. Before founding Fortuna Advisors, he was a partner at Stern Stewart and a managing director at Credit Suisse.

Michael Chew is an associate at Fortuna Advisors. He holds a master's degree in finance from the University of Rochester–Simon Business School.

Michael Chew is an associate at Fortuna Advisors. He holds a master's degree in finance from the University of Rochester–Simon Business School.