Uncertainty and volatility are running rampant right now on the global political and economic stage. The world seemed less tumultuous in mid-2016, when the Association for Financial Professionals drafted its latest risk survey. The AFP's decision to focus that survey on geopolitical risk now seems prescient.

Uncertainty and volatility are running rampant right now on the global political and economic stage. The world seemed less tumultuous in mid-2016, when the Association for Financial Professionals drafted its latest risk survey. The AFP's decision to focus that survey on geopolitical risk now seems prescient.

Respondents to the survey included 480 treasurers, assistant treasurers, CFOs, controllers, and vice presidents of finance. Treasury & Risk recently sat down with Craig Martin, the AFP's director of executive programs and treasury practice lead, to discuss the key takeaways from the research report.

Recommended For You

T&R: What are the biggest surprises to come out of this research?

Craig Martin: Broadly speaking, I'm not surprised by any of the results. The ability to forecast earnings continues to be an issue. Half of our survey respondents [49 percent] said they're exposed to more earnings uncertainty than they were three years ago, while only 11 percent said they're exposed to less uncertainty.

What I find even more interesting is that more than half of respondents expect forecasting risk to be even more difficult three years from now. Part of me wonders how much more difficult it can get, with everything that's going on in the world. What's going to happen in the South China Sea? What's going to happen with North Korea and nukes? The Middle East is literally burning, if you look at pictures of Aleppo, Syria.

The world is very difficult right now. I've been in the markets for 40 years, and I'm not sure I've ever seen a time of such disconcertedness.

T&R: Only 19 percent of survey respondents expect geopolitical risk to be a key factor driving their organization's earnings uncertainty in the next three years. It looks like your survey respondents are more concerned about tougher competition (cited as a key risk factor by 40 percent of respondents), customer satisfaction and retention (33 percent), and U.S. political or regulatory uncertainty (32 percent).

CM: It's interesting that in an election year, finance professionals believed competition would have a greater impact on their organizations' earnings than would uncertainty around the U.S. political environment. I think that's a result of the interconnectedness of the world. The "Global Risks Report 2017" from the World Economic Forum finds that the interconnectedness of geopolitics, technological advances, global economic integration, social instability, and climate change means that the manifestation of one risk is increasingly likely to influence others, with unforeseeable impacts. With technology, the world is becoming more and more of a global marketplace, which means companies are having to adapt and compete in new ways. Technological change can be very disruptive, and can make it hard to grasp everything that is happening in your competitive environment.

CM: It's interesting that in an election year, finance professionals believed competition would have a greater impact on their organizations' earnings than would uncertainty around the U.S. political environment. I think that's a result of the interconnectedness of the world. The "Global Risks Report 2017" from the World Economic Forum finds that the interconnectedness of geopolitics, technological advances, global economic integration, social instability, and climate change means that the manifestation of one risk is increasingly likely to influence others, with unforeseeable impacts. With technology, the world is becoming more and more of a global marketplace, which means companies are having to adapt and compete in new ways. Technological change can be very disruptive, and can make it hard to grasp everything that is happening in your competitive environment.

At the same time, political and regulatory uncertainty was the third leading factor driving survey respondents' earnings uncertainty going forward. This is particularly noteworthy because our survey went out before the U.S. election happened. Even before Trump won the presidency, companies were very interested in finding out which regulations would be unwound.

And on top of that, you have questions about interest rates, which was the fourth most frequently cited factor driving earnings uncertainty. We're starting to come out of the world of easy monetary policy, and I don't think it's just going to be the United States. I think the European Union will cut back on its purchases, and Japan will as well. It's time to wean ourselves off of zero-interest-rate policy and get back to something normal; it will be painful, but we need to do it.

It's also worth noting that currency risk ranked fifth in our survey. The currency markets are extremely volatile, and I project that they will remain volatile as Britain prepares to exit the EU.

It's also worth noting that currency risk ranked fifth in our survey. The currency markets are extremely volatile, and I project that they will remain volatile as Britain prepares to exit the EU.

To the 51 percent of respondents who expect risk to get even more difficult to forecast over the next three years, I would ask how it can get more difficult than it is now, because accurate forecasting has become almost impossible.

T&R: If geopolitical volatility continues to increase, what can companies do to reduce uncertainty in their financials?

CM: Some companies are using advanced analytics tools. For example, a company called Predata has developed a system that predicts volatility in specific countries or markets based on trends in social media conversations. There are ways in which technology can help you understand better what is going on in the external world, which means you'll be less surprised and be better prepared.

T&R: Your survey reveals a number of benefits that respondents think companies can achieve by effectively integrating risk data and analytics into their organization, including improving risk identification, informing the overall business strategy, and enhancing risk mitigation.

CM: Yes, improving risk identification was cited by 50 percent of respondents, and companies definitely need to put more energy into identifying risks. One of the first steps is to understand your corporate risk appetite. You have to start by defining what risks you're willing to absorb and what risks you want to lay off, whether through insurance, self-insurance, derivatives, or in some other way.

T&R: Is analytics technology a driver for many companies to define their risk appetite and take a more rigorous approach to risk management?

CM: It's one driver, but think about the history of enterprise risk management (ERM). It started as a buzzword; companies would put an ERM program in place and generate a big report that would just sit on a shelf. As a result, the whole idea of ERM got pooh-poohed.

But then companies started looking beyond the technologies and metrics. Many of them got rid of their chief risk officer because they realized they needed to make risk management the responsibility of every division and business unit head across the organization. Now ERM is a conversation that takes place throughout the company. Risk analytics should be integrated into corporate operations in much the same way.

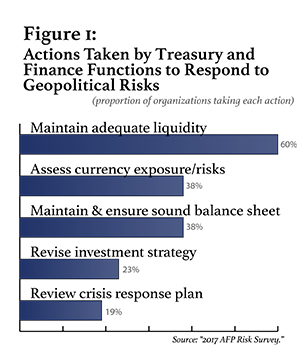

T&R: You also asked in this survey about what actions companies are taking to respond to the potential impacts of geopolitical risks. (See Figure 1.) Were you surprised by these results?

CM: Not surprised at all. The top three answers here are three of the corporate treasurer's primary responsibilities. We recently hosted a webcast that looked at how companies could prepare for black swan events. One way we discussed is having a sound capital structure. Another is to ensure that the company has access to adequate liquidity. That means more than just having a certain amount of cash on hand. It's about access to capital markets, access to bank loans, knowing where you can go if your usual sources of liquidity dry up.

Look at what happened in 2008 when the commercial paper market collapsed. Some companies were huge CP issuers on a daily basis, and all of a sudden the market was gone. Uh oh. And then some banks cut off companies' access to their lines of credit. What's the point of having a line of credit if you can't access it? Making sure the company has access to adequate liquidity is a core treasury responsibility, and it's really one of the best ways to cope with geopolitical uncertainty.

Look at what happened in 2008 when the commercial paper market collapsed. Some companies were huge CP issuers on a daily basis, and all of a sudden the market was gone. Uh oh. And then some banks cut off companies' access to their lines of credit. What's the point of having a line of credit if you can't access it? Making sure the company has access to adequate liquidity is a core treasury responsibility, and it's really one of the best ways to cope with geopolitical uncertainty.

T&R: Your research report also recommends managing geopolitical risk by managing credit risk, building resilient supply chains, and protecting your people.

CM: These are fairly obvious, and they're activities treasury and finance professionals should undertake regardless of the external economic climate. But right now these responsibilities might need more attention than usual from treasury leadership.

It's also important to think through the possible ramifications of political changes currently under way. For example, if Trump and Congress are able to lower corporate taxes and include a one-time repatriation window in their tax reform package, a lot of the cash that U.S. companies currently have sitting offshore will likely be repatriated. If that money comes onshore, and because of permanently lower taxes it stays onshore, what does that do to U.S.-based companies' capital spending and bank balances in Europe? How does that impact trade?

If U.S. tax reform comes about, it could cause a significant shift in cash management and cash flows around the world. What does that mean for the financial sector in Europe? What does that mean for U.S. corporates' counterparty risk abroad? What about their supply chains? If one vendor has trouble accessing bank financing, for example, will you lose access to component parts you need to build your product? Companies need to be considering these possibilities today. Regular geopolitical-focused scenario planning is one way to accomplish this.

T&R: And what should companies be doing to protect their people?

CM: Well, again, the world's a global marketplace now, so many U.S. companies have people all over the world. As the world becomes more dangerous, the key is to ensure the company has good communication. This may or may not sit in the treasury or finance function, but it's imperative that during a crisis, the company must have appropriate business continuity plans in place. These plans need to be tested, they need to include a communication tree for all your people, and they need to let everyone know what to do in the event of a crisis.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.