As the coronavirus spread across the globe in March, it led to a liquidity crisis that was without precedent. Even U.S. Treasuries—often considered the most liquid investments on the planet—became difficult to sell. The Federal Reserve has, for now, alleviated the worst of the crisis. But for institutional investors such as pension plans, which regularly need to pay their members, liquidity will remain a pressing worry.

This problem is likely to get deeper over time, and not simply due to underlying market dynamics. Many pension plans are now cash flow negative—in other words, they are paying out more than they are taking in on an ongoing basis.

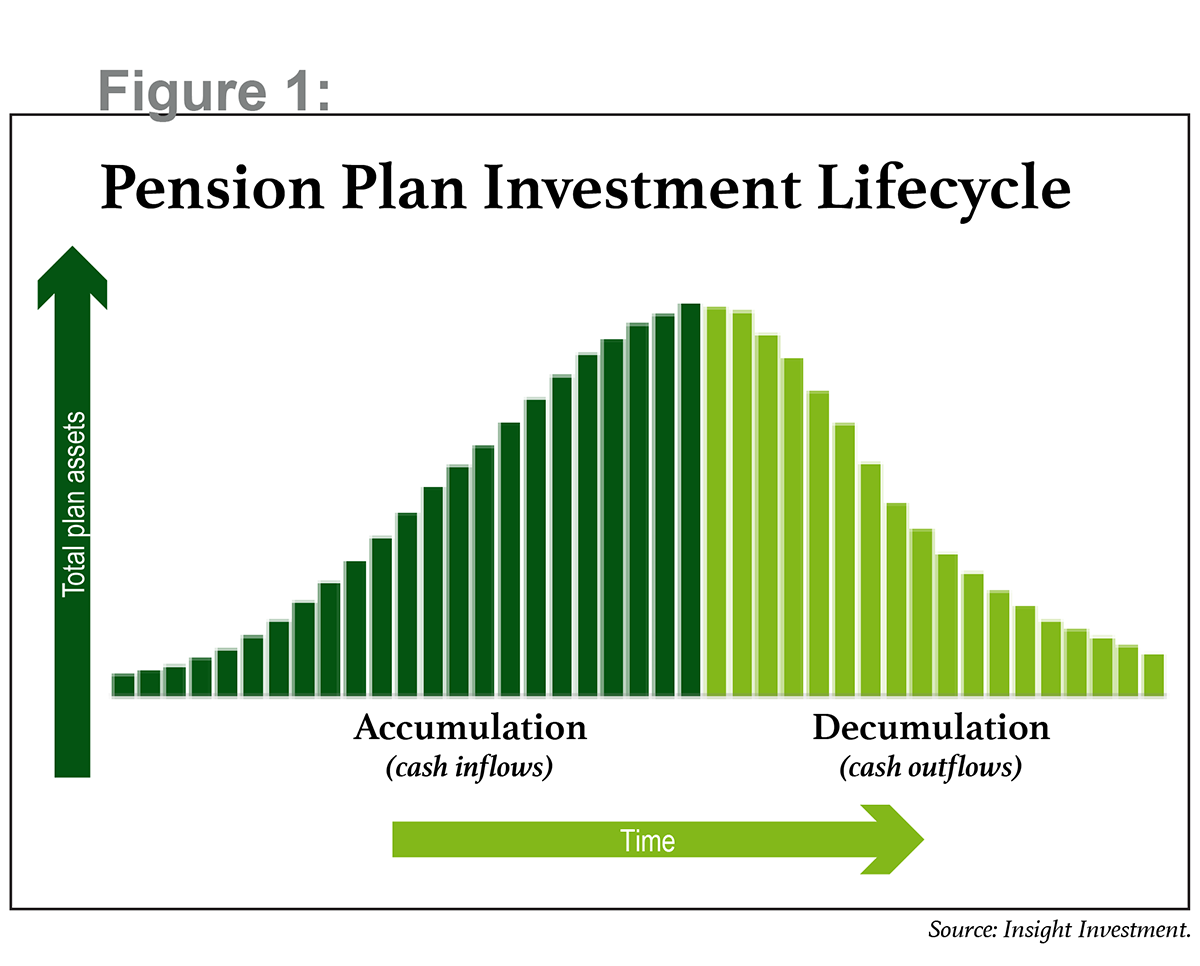

In addition, more and more retirement programs are moving from the "accumulation" phase of their lifecycle to the "decumulation" phase. They are closing the pension to new participants and beginning to spend down the asset base accumulated earlier in the plan's lifecycle. According to an analysis recently conducted by Insight Investment, 87 percent of traditional defined-benefit pension plans are now cash flow negative.1

This is an important, and permanent, inflection point that can resemble an armadillo's back (see Figure 1). It is also a situation that poses vital challenges for defined-benefit plan sponsors.

What's the Big Deal?

The combination of negative cash flows and difficult liquidity conditions can undermine a plan in powerful ways:

- Investment managers may be forced to sell assets at inopportune times, in an effort to meet obligations. As the recent crisis has shown, trying to sell even safe assets like Treasuries can be expensive when market liquidity is challenged. Potentially even worse, imagine being forced to sell equities during a market decline like the one we saw in late March.

- Percentage returns translate to fewer dollars as the plan's asset levels shrink. As a "decumulating" plan has a shrinking asset base, percentage returns will translate to lower dollar returns. For example, assume your asset base shrinks from $100 million in 2010 to $80 million in 2020. A 5 percent return would have generated $5 million in 2010, but now it produces only $4 million. Negative cash flows can make it progressively harder for a plan to meet investment-return objectives.

Unfortunately, economic theories for managing liquidity and decumulation are scarce. Since the 1940s and '50s, pension plans have spent most of their lives accumulating assets. This was also an era that heralded the emergence and development of revolutionary finance theory. You know the names: Markowitz, Tobin, Fama, French, Sharpe, Treynor, Modigliani, Merton, Miller, Black, Scholes, and many others provided a wealth of innovative thinking for investment management success. However, all their (often Nobel Prize–winning) research shared two common characteristics: long-term horizons and a focus on the "accumulation" stage.

Special challenges emerge in the face of more immediate cash flow needs. And plans are left with little research to draw on for decumulation amid practical liquidity constraints. Finance theory is now enjoying another period of innovation with input from chaos theory, nonlinear dynamics, and complexity theory, but we are at an early stage.

The reality is simple: Plans cannot afford to rely on conventional wisdom. They need practical, process-driven solutions for negative cash flows and management of pension liquidity.

A Potential Solution

Regular and reliable income streams are the most dependable form of liquidity for a pension plan, through any future liquidity crisis. Therefore, plans may wish to consider a cash flow–driven investment (CDI) approach, focusing on investments that deliver relatively high contractual coupons with a high degree of certainty.

We believe CDI can form an important pillar of a liability-driven investing (LDI) strategy. A typical LDI approach focuses on making sure the market value of a plan's assets and the present value of its liabilities move in lockstep. Too often, however, these calculations fail to factor in the timing of cash flows. The recent crisis has shown that assuming the markets will always offer perfect liquidity could really compromise the hard work of putting together an LDI strategy.

The goal of CDI is squarely aimed at addressing the liquidity part of the equation by generating cash inflows to pay out benefits from investments, such as coupons from bonds, dividends from equities, or cash payments from real estate investments. CDI strategies aim to avoid relying on interventions, such as periodic rebalancing or forced selling, to generate liquidity.

Pension plan sponsors may consider a wide range of scenarios in an effort to find the right one to meet their cash flow needs. We have three recommendations for designing an effective CDI investment strategy:

1. Consider the structured credit market, which includes asset-backed securities (such as mortgage-backed securities). Since the crisis began and credit spreads widened, this market has begun to offer a significant spread pickup, of up to 300 basis points (bps) over LIBOR for AAA or AA credit risks.2 Given the fact that these assets are secured against collateral and subject to structural protections (such as debt covenants and credit enhancement), the highest-quality instruments can also offer a high degree of safety.

2. Seek higher returns elsewhere within the current asset allocation. If a CDI strategy can effectively address the plan's cash obligations, then the plan's other assets can be focused on a return-seeking/growth investment strategy because they do not need to be liquid enough to be sold when obligations come due.

Having a dedicated CDI strategy opens the door to having some less-liquid—and, theoretically, higher-yielding—assets within the plan's asset allocation. For example, where a plan may have previously held public equities exclusively, it might now consider exposure to private equity within its equity allocation. Thinking this way can also help reduce concerns about cash drag.

3. Hold a minimum level of liquidity. If a plan sponsor always has a "pool" of liquidity designed to meet plan outflows, the cash inflows generated by investments will not need to match obligations exactly. Instead, income from investments will continuously top up the pool. This provides some freedom regarding selection of appropriate assets for the CDI portfolio, often providing the leeway to purchase more attractive assets.

Confronting the Armadillo

Based on our observations, pension plans with structural CDI solutions were best placed to withstand the liquidity crisis that occurred in March and April of this year. As investors rushed to sell assets, some of our clients even had the luxury of playing offense rather than defense, adding exposure to certain assets at cheaper valuations.

Delivering on cash obligations cuts to the heart of the pension promise. Negative cash flows and market liquidity are important considerations that can impact every part of a plan's investment strategy.

The time for vital conversations is now. Pension plan sponsors need thoughtful solutions for successfully descending the armadillo's back. We believe a CDI approach can simultaneously improve a plan's overall efficiency and the certainty of reaching its long-term outcome, even in the face of substantial volatility.

Opinions expressed herein are as of June 23 and subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Jack Boyce is head of distribution, North America, at Insight Investment.

Jack Boyce is head of distribution, North America, at Insight Investment.

1. Source: Bloomberg, Insight Investment calculation. Based on 100 largest defined-benefit plans by PBO. Net cash flow estimated by difference between GAAP deficit and expected five-year benefit payments.

2. JPMorgan and Bank of America Merrill Lynch, May 2020.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.